MADRID, 9 Abr. (EUROPA PRESS) -

On April 10, 1998, Ulster ended three decades of conflict with a historic agreement. The Belfast Accords, renamed for posterity the Good Friday Accords after the date they were signed, marked the beginning of the end of sectarian clashes stemming from a consensus that is now shaky, shaken by the political fallout from the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union.

The conflict dates back to the 1920s, when the island of Ireland was divided between an independent country of the same name and a northern area that was still linked to the United Kingdom. The unionist theses then triumphed, to the detriment of those of the republicans, who wanted to integrate into independent Ireland.

Political and social discrepancies led to the creation of armed groups a decade later: on the part of the unionists, the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force arose, while on the rival side the Irish Republican Army, known by the English acronym IRA, was created. .

Los Problemas ('The Troubles', in English) began, the euphemism by which a conflict is known that claimed more than 3,500 lives for three decades, until the signing of the Good Friday Agreements.

The main challenge of said text was to draw a new framework for political coexistence that would also reflect the complex social fabric of a people split in two, with divisions established even in the religious sphere -- the unionists are mostly Protestants, while the Republicans identify with Catholicism.

The Agreements laid the foundations for a framework of respect between the two parties and, in the political arena, gave rise to a new Parliament based in Belfast and a government that was bound to be a coalition. The nationalists, led by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), and the republicans, led by Sinn Féin, the political arm of the IRA, were forced to sit at the same table.

The armed groups renounced the armed struggle and there were releases, while London agreed to renounce a large part of its military presence as a gesture of détente, in a practically festive atmosphere that transcended political protocol and in which public figures took part.

The United States, then headed by Democrat Bill Clinton, acted as mediator in these negotiations, which concluded with the signing of the two main political leaders of Ireland and the United Kingdom: Tony Blair for the British side and Bertie Ahern for the Irish side.

The Norwegian Committee recognized these political efforts in 1998 with the Nobel Peace Prize, personified in the figures of the Irish political leader John Hume and the Northern Irishman David Trimble. The jury understood that their work would not only allow peace in Northern Ireland, but would serve to "inspire" other peaceful solutions to conflicts of various kinds around the world.

The agreement, however, did not mean the complete end of the violence, since although the main armed leaders agreed to lay down their arms, certain divisions were generated within the IRA that led to the formation of several divisions, with subgroups that They are still active today and are still a threat in the eyes of the authorities.

In fact, the British Government decided this past March to raise the anti-terrorism alert level to serious, which means considering attacks "very likely" to take place. This is how he responded to the murder in February of a police officer, John Caldwell, shot dead after attending a children's soccer game. The attack was claimed by the New IRA.

An independent investigation published in 2018 estimated 158 fatalities due to paramilitary activities after the signing of the Good Friday Agreements.

Northern Ireland today is not the same as it was 25 years ago. In September 2022, the census showed for the first time that there were more people who identified themselves as Catholics than Protestants, and in the parliamentary elections in May, for the first time, Sinn Féin won first place, to the detriment of the DUP, which has always been he had arrogated the position of chief minister and, therefore, the baton of the Government.

All this in a context marked since 2016 by Brexit. In June of that year, a majority of British citizens -also in Northern Ireland- supported a referendum on the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union, forcing them to redraw a framework of relations that had among its thorniest points the border on the island of Ireland.

The British Government and the European Commission devised what is known as the Northern Ireland Protocol, annexed to the Brexit agreements and which removed the specter of a 'hard border'. It allowed Northern Ireland to remain linked to the common European market, but required the establishment of a series of controls on trade with England, Scotland and Wales.

The unionist suspicion towards these controls, alleging that it limits fluid relations with the rest of the United Kingdom, has led to a political blockade in Northern Ireland, to the point that this area has lacked a government since the last elections. The DUP has refused to facilitate institutional functioning and agree to a new coalition until their demands are taken into account.

The three-way pulse resulted in the Windsor Framework in March of this year, a new text that simplifies these controls and that has the approval of the majority of the deputies in the House of Commons. The DUP, however, has asked for time to examine all the details and derivatives and has yet to decide whether to take the final step to build bridges with Sinn Féin again.

Exploring Cardano: Inner Workings and Advantages of this Cryptocurrency

Exploring Cardano: Inner Workings and Advantages of this Cryptocurrency Seville.- Economy.- Innova.- STSA inaugurates its new painting and sealing hangar in San Pablo, for 18 million

Seville.- Economy.- Innova.- STSA inaugurates its new painting and sealing hangar in San Pablo, for 18 million Innova.- More than 300 volunteers join the Andalucía Compromiso Digital network in one month to facilitate access to ICT

Innova.- More than 300 volunteers join the Andalucía Compromiso Digital network in one month to facilitate access to ICT Innova.-AMP.- Ayesa acquires 51% of Sadiel, which will create new technological engineering products and expand markets

Innova.-AMP.- Ayesa acquires 51% of Sadiel, which will create new technological engineering products and expand markets Khan is re-elected mayor of London and underpins Labor's victory in local elections

Khan is re-elected mayor of London and underpins Labor's victory in local elections Felipe VI swears the flag again 40 years later at the AGM with Princess Leonor as a witness

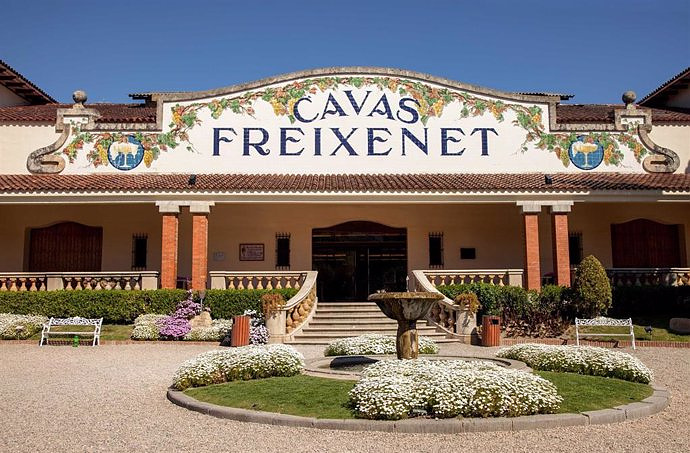

Felipe VI swears the flag again 40 years later at the AGM with Princess Leonor as a witness Freixenet and unions agree to reduce working hours by 20-50% this year due to the drought

Freixenet and unions agree to reduce working hours by 20-50% this year due to the drought STATEMENT: Nearly 400 people participate in the II Family Support Conference at UIC Barcelona

STATEMENT: Nearly 400 people participate in the II Family Support Conference at UIC Barcelona How Blockchain in being used to shape the future

How Blockchain in being used to shape the future Not just BTC and ETH: Here Are Some More Interesting Coins Worth Focusing on

Not just BTC and ETH: Here Are Some More Interesting Coins Worth Focusing on A sensor system obtains the fingerprint of essential oils and detects if they have been adulterated

A sensor system obtains the fingerprint of essential oils and detects if they have been adulterated Faraday UPV presents the 'Origin' rocket to exceed 10 km of flight: "It is the beginning of the journey to space"

Faraday UPV presents the 'Origin' rocket to exceed 10 km of flight: "It is the beginning of the journey to space" The Generalitat calls for aid worth 4 million to promote innovation projects in municipalities

The Generalitat calls for aid worth 4 million to promote innovation projects in municipalities UPV students design an app that helps improve the ventilation of homes in the face of high temperatures

UPV students design an app that helps improve the ventilation of homes in the face of high temperatures A million people demonstrate in France against Macron's pension reform

A million people demonstrate in France against Macron's pension reform Russia launches several missiles against "critical infrastructure" in the city of Zaporizhia

Russia launches several missiles against "critical infrastructure" in the city of Zaporizhia A "procession" remembers the dead of the Calabria shipwreck as bodies continue to wash up on the shore

A "procession" remembers the dead of the Calabria shipwreck as bodies continue to wash up on the shore Prison sentences handed down for three prominent Hong Kong pro-democracy activists

Prison sentences handed down for three prominent Hong Kong pro-democracy activists ETH continues to leave trading platforms, Ethereum balance on exchanges lowest in 3 years

ETH continues to leave trading platforms, Ethereum balance on exchanges lowest in 3 years Investors invest $450 million in Consensys, Ethereum incubator now valued at $7 billion

Investors invest $450 million in Consensys, Ethereum incubator now valued at $7 billion Alchemy Integrates Ethereum L2 Product Starknet to Enhance Web3 Scalability at a Price 100x Lower Than L1 Fees

Alchemy Integrates Ethereum L2 Product Starknet to Enhance Web3 Scalability at a Price 100x Lower Than L1 Fees Mining Report: Bitcoin's Electricity Consumption Declines by 25% in Q1 2022

Mining Report: Bitcoin's Electricity Consumption Declines by 25% in Q1 2022 Oil-to-Bitcoin Mining Firm Crusoe Energy Systems Raised $505 Million

Oil-to-Bitcoin Mining Firm Crusoe Energy Systems Raised $505 Million Microbt reveals the latest Bitcoin mining rigs -- Machines produce up to 126 TH/s with custom 5nm chip design

Microbt reveals the latest Bitcoin mining rigs -- Machines produce up to 126 TH/s with custom 5nm chip design Bitcoin's Mining Difficulty Hits a Lifetime High, With More Than 90% of BTC Supply Issued

Bitcoin's Mining Difficulty Hits a Lifetime High, With More Than 90% of BTC Supply Issued The Biggest Movers are Near, EOS, and RUNE during Friday's Selloff

The Biggest Movers are Near, EOS, and RUNE during Friday's Selloff Global Markets Spooked by a Hawkish Fed and Covid, Stocks and Crypto Gain After Musk Buys Twitter

Global Markets Spooked by a Hawkish Fed and Covid, Stocks and Crypto Gain After Musk Buys Twitter Bitso to offset carbon emissions from the Trading Platform's ERC20, ETH, and BTC Transactions

Bitso to offset carbon emissions from the Trading Platform's ERC20, ETH, and BTC Transactions Draftkings Announces 2022 College Hoops NFT Selection for March Madness

Draftkings Announces 2022 College Hoops NFT Selection for March Madness